Operational Research in Pompeii, 79CE

In my former blog, I wrote about the logistics of transporting monumental stone from Egypt to Rome during the time of the Roman Empire (Logistics in Ancient Egypt)

Now I want to return to that era with some more reflections.

The Roman town of Pompeii was overwhelmed in 79CE by the eruption of the nearby volcano, Mount Vesuvius. The site is famous for the preservation of many buildings, including the wall paintings and interior decoration, and for the experience of wandering around a town frozen in time, nearly two thousand years ago. Needless to say, the remains have been the subject of many archaeological excavations and countless academic (and popular) accounts of aspects of the town and its life. But, as far as I am aware, nobody has yet applied O.R. to some of the analysis of the remains. So, here are two suggestions.

First, there is the question of the population of the town. The excavations have uncovered many dwelling houses and businesses. But as there were no census records, it is not clear how dense the population was. Contemporary writers did not explain in much detail the structure of different households, so estimating the population from the housing stock is tricky. And the excavations only cover some of the site - were there people living in houses outside the walls? So another approach has been to look at the hinterland. How much agricultural land was within the vicinity of Pompeii? How much land, used for different types of agriculture - cereals, vineyards, orchards, livestock - is needed to support a town? There have been some estimates of this, but they are hindered by the limited knowledge of the farmland. Farms would have been scattered, and many are now probably buried under the soil of modern farms, villages and roads. (more is known about vineyards than most other agriculture because vineyards need stone presses and other equipment, which survives intact). O.R. could help relate these two approaches and might offer a third way of reaching an estimate, based on transport patterns and gravity models. Would it be feasible for farmers to transport their wares to the town, and distribute them in the given network of streets? How about an interactive visual simulation of the streets? And from that, work out the daily amount of food that the town would need and the streets could absorb.

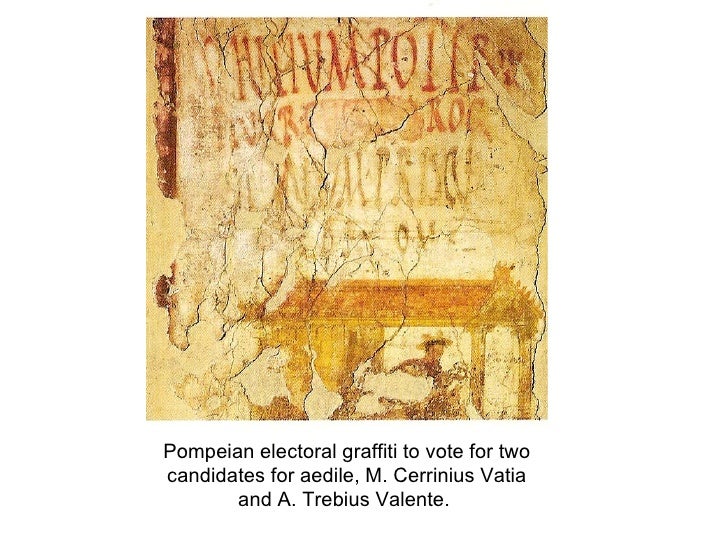

Second, and this does build on another O.R. application to an archaeological problem. On the walls of Pompeii, there are many pieces of graffiti. Some relate to businesses, others are idle "Julius was here". But a significant number relate to elections for civic office. Where there is only one, it is possible to estimate a date based on the weathering of the paint. In many places, successive "posters" have been painted to obliterate or overlap earlier ones. Which implies an order of elections. The problem of sorting partially ordered data into a best fit series has been used to sequence ceramics in several archaeological studies, so the methodology is there.

Now I want to return to that era with some more reflections.

The Roman town of Pompeii was overwhelmed in 79CE by the eruption of the nearby volcano, Mount Vesuvius. The site is famous for the preservation of many buildings, including the wall paintings and interior decoration, and for the experience of wandering around a town frozen in time, nearly two thousand years ago. Needless to say, the remains have been the subject of many archaeological excavations and countless academic (and popular) accounts of aspects of the town and its life. But, as far as I am aware, nobody has yet applied O.R. to some of the analysis of the remains. So, here are two suggestions.

First, there is the question of the population of the town. The excavations have uncovered many dwelling houses and businesses. But as there were no census records, it is not clear how dense the population was. Contemporary writers did not explain in much detail the structure of different households, so estimating the population from the housing stock is tricky. And the excavations only cover some of the site - were there people living in houses outside the walls? So another approach has been to look at the hinterland. How much agricultural land was within the vicinity of Pompeii? How much land, used for different types of agriculture - cereals, vineyards, orchards, livestock - is needed to support a town? There have been some estimates of this, but they are hindered by the limited knowledge of the farmland. Farms would have been scattered, and many are now probably buried under the soil of modern farms, villages and roads. (more is known about vineyards than most other agriculture because vineyards need stone presses and other equipment, which survives intact). O.R. could help relate these two approaches and might offer a third way of reaching an estimate, based on transport patterns and gravity models. Would it be feasible for farmers to transport their wares to the town, and distribute them in the given network of streets? How about an interactive visual simulation of the streets? And from that, work out the daily amount of food that the town would need and the streets could absorb.

Second, and this does build on another O.R. application to an archaeological problem. On the walls of Pompeii, there are many pieces of graffiti. Some relate to businesses, others are idle "Julius was here". But a significant number relate to elections for civic office. Where there is only one, it is possible to estimate a date based on the weathering of the paint. In many places, successive "posters" have been painted to obliterate or overlap earlier ones. Which implies an order of elections. The problem of sorting partially ordered data into a best fit series has been used to sequence ceramics in several archaeological studies, so the methodology is there.

Comments

Post a Comment